What if the Government Actually is Coming for Your Bitcoin?

As I discussed previously, the pretext which many in the Bitcoin community use to stoke anxiety about looming governmental confiscation of bitcoin relies on a misapplication of U.S. history from the 1930s. In brief, FDR’s 1933 executive orders and resulting federal legislation prohibiting the “hoarding of gold coin, gold bullion, and gold certificates” arose in the depths of the Great Depression when the dollar was backed by gold at a fixed price determined by Congress. It was an age before “infinite dollar” when the number of dollars in the economy was constrained by the number of ounces of gold held by the U.S. Treasury. The government couldn’t freely expand the money supply by simply printing it into existence. One cannot with intellectual integrity draw a straight line from the gold orders of the 1930s to invoke fear that the U.S. government would require personal bitcoin holders to surrender their bitcoin.

But rationale and understanding of history be damned! Let’s pursue the (remote, at best) possibility that a future series of events mandate the surrender of bitcoin to the U.S. Treasury. What happens if I’m wrong, or if the law-abiding bitcoiner somehow finds themselves on the wrong side of the government?

A disclaimer interlude

I owe the reader the following disclaimer:

I am a licensed attorney, admitted to practice law in four states. I had an active law practice before starting my present enterprise and am no longer in the active practice of law. My area of focus for 25 years was the application of estate planning, asset protection, and tax law for highly affluent people. I am retired from the practice of law. I cannot be hired by anyone to provide legal advice or representation.

It is imperative that the reader understand that nothing in this post–or in any other post I write–constitutes legal, tax, or financial advice. I write to educate, to provoke inquiry, and at times, to entertain. I give no legal advice whatsoever. We have no attorney-client relationship and if you engage in comments or reach out to me to discuss anything here, neither your comments nor any response I might offer would be protected by attorney-client privilege. (Not to mention the fact that the comments are public anyway.)

Any estate planning, asset protection, or other legal-related content I write about will be oversimplified and incomplete. Do not rely on anything you read online–here or anywhere else–to make any decisions concerning your property or other legal matters. Always rely on tailored, independent guidance from professionals with whom you have a formal engagement.

Now back to the matter at hand.

CYA–Covering Your Ass(ets)

The concern about the government coming for someone’s bitcoin–or any other asset for that matter–speaks to the broader issue of protecting assets from the claims of potential creditors. Many refer to this practice as “creditor protection”. Of course, this term makes no sense because one generally doesn’t seek to “protect” one’s creditors. We will broadly refer to the practice of “asset protection” because after all, it’s the assets we seek to protect.

Individuals with consequential wealth–and particularly those in high profile or high liability professions–are often justifiably concerned that third parties may initiate litigation that exposes their wealth to risk of loss. As a general rule, a successful plaintiff “steps into the shoes” of the unsuccessful defendant. To the extent the defendant has unilateral control over their assets, those assets are at risk of forfeiture to the plaintiff. This is as true for bitcoin as for any other type of asset.

Asset protection is not illegal per se. HOW assets are protected and WHEN the protective measures are taken determine whether the action was legal or illegal. We’ll get to this issue in some level of detail but first…

An Historic Primer on Asset Protection

Almost every developed jurisdiction prohibits transfers made with the intent to “hinder, delay, or defraud” one’s creditors. Within the U.S., these prohibitions are most explicitly outlined in the Uniform Fraudulent Transfer Act or its successor, the Uniform Voidable Transactions Act, versions of which are codified in most states. Similar provisions exist under the U.S. Bankruptcy Code.

The origin of this prohibition dates to English common law enacted in 1571. Broadly referred to as the “Statute of Elizabeth”, the Fraudulent Conveyances Act 15711 outlawed and set aside any transfers of property which had the intent to “delay, hinder or defraud creditors”. The law applied to all transfers, including transfers to family members, “feoffments” (a precursor to modern trusts for real estate, which would give rise to general trust law concepts), gifts or sales for less than full value, and any other contrivance that attempted to shift assets beyond the reach of creditors.

The 1571 Statute of Elizabeth lives on in the Fraudulent Transfer Act, Voidable Transactions Act, the U.S. Bankruptcy Code, and the laws of many other jurisdictions.

But a growing number of jurisdictions in the U.S. and some offshore jurisdictions have either softened the impact of the Statute of Elizabeth or eliminated it altogether. Within the U.S., states like Nevada, South Dakota, Wyoming, Ohio, New Hampshire, and roughly a dozen more allow individuals to establish various forms of irrevocable trusts and other strategies in order to shield assets from the claims of future potential creditors.2 The level of protection and the applicability of the various forms of “Domestic Asset Protection Trusts” (DAPTs) ranges widely and is not available to everyone.

Outside the U.S., some jurisdictions have entirely abolished the Statute of Elizabeth and offer robust asset protection for property held in appropriate structures. For technical and diplomatic reasons, I won’t go into written detail here, but suffice to say that those non-U.S. jurisdictions are attractive because they refuse to recognize court orders entered in the U.S. In order to penetrate those more favorable offshore structures, a creditor must litigate its claim against the trust in the trust’s offshore jurisdiction. This creates a significant hurdle many plaintiffs simply won’t pursue.

Importantly, the application of the Statute of Elizabeth and its progeny extends to void transactions that are otherwise legal. For example, if one has assets that are not covered by a homestead exemption or is otherwise unprotected, but seeks to convert nonexempt property to an exempt form of property after a claim arises, the property will not be protected from the creditor’s claim. Likewise, one cannot shift assets into another asset protected strategy (e.g., irrevocable trust, LLC) after a creditor’s claim has arisen. Sorry pal, you’re too late. The strategy will be set aside and more consequences will follow.

An Unsanctioned, Uncertain Way

A Peter Pan mentality is alive and all too well in the bitcoin–and definitely within broader “crypto-anarchist”–community. Bitcoin and its blockchain progeny is built on code, which can be applied in creative and sophisticated ways to alter how the asset can operate in its digital environment. For all practical purposes, bitcoin and crypto are largely unconstrained in how users structure wallets, manage private keys, and apply programmatic scripting to alter access to blockchain assets. Bitcoin’s programmability makes it tempting to eschew legally proven methods of protection for creative solutions that aren’t recognized by law.

Some of the idealistic advice on the internet includes sharding and geographically distributing analog private key material (e.g., paper wallets, metal seed phrase plates) participating in “CoinJoin” transactions to mix one’s bitcoin with that of others, creating time lock scripting or other coding to disable access to bitcoin, using offshore or non-KYC bitcoin ATMs to avoid leaving a transaction trail. Using decentralized exchanges (DEXs) to convert bitcoin to more privacy-enabled cryptoassets are also touted as effective means to hide the source and destination of funds.

These methods aren’t illegal on their own. There are perfectly legitimate reasons to optimize for privacy and these should be celebrated and expanded, not vilified. Similarly, engaging in transactions with cash isn’t illegal either. Many law-abiding people prefer to use cash specifically to ensure privacy in their transactions. But privacy-enhancing transactions are subject to higher levels of scrutiny and when they’re used to hide assets from the reach of creditors (including Uncle Sam), they can constitute circumstantial evidence of an intent to break the law. It’s like trying to stuff your private keys into your “prison wallet” and hoping the warden never finds out. (If you know the reference, I’m sorry; the metaphor was irresistible. If you don’t know the reference, please don’t look it up.)

Someday the warden will find out. If the scheme doesn’t pinch the cheater directly, it will pinch the people the cheater gave their bitcoin to. Someday someone will want to use the “hidden bitcoin” for something in Normieland. They’ll want to buy a house, send a kid to college, or otherwise enjoy the benefits that come from meaningful wealth. When the hidden bitcoin eventually surfaces, the government will be waiting.

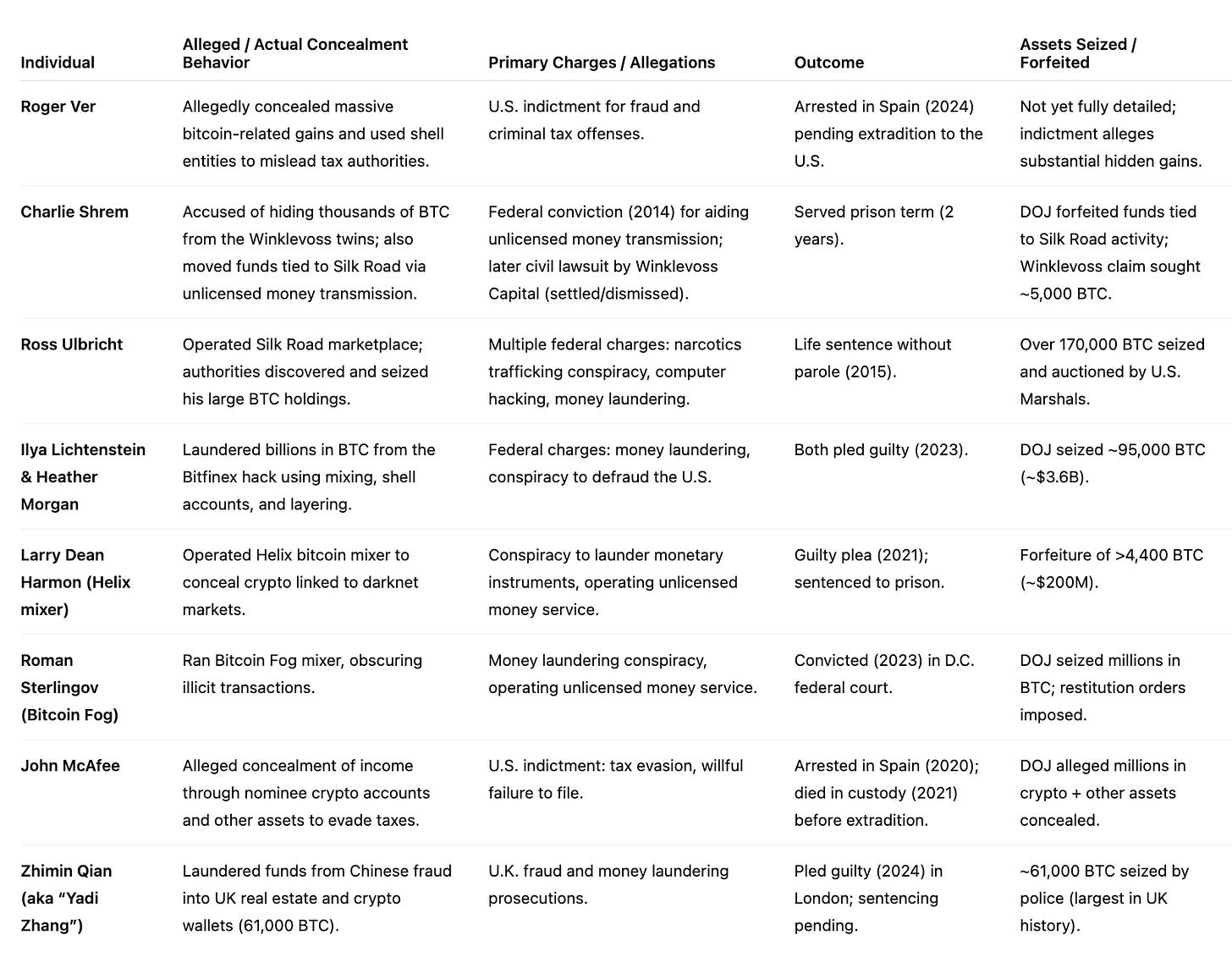

If this just feels like extreme fear mongering, it isn’t. Plenty of others have learned their lessons the hard way. Obfuscation methods (mixers, nominee accounts, complex scripts) routinely lead to money-laundering charges and forfeiture, even when defendants never “cash out.”3 Authorities have seized and recovered multi-billion-dollar troves of BTC from concealed or laundered holdings—both in the U.S. and abroad.4 With the help of a few chatbots, I assembled a brief table of some of the more notable cases and attached it at the end of this article.

The Reliable Way for Intelligent Wealth

There are perfectly lawful ways to shift assets beyond the reach of creditors. In each instance, there can be no half-measures; it’s imperative that any strategy be carefully assessed and assiduously pursued to completion. In seeking to insulate assets from the claims of potential creditors, a wide range of strategies provides varying levels of protection. These include:

Basic “homestead” exemptions–Within the United States, each jurisdiction provides a set of statutory protections against claims. These range from very miserly (e.g., New Jersey, Pennsylvania) to quite generous (Texas, Florida), but no state currently provides statutory asset protection for bitcoin or other bearer assets beyond very modest values.

Corporate veils–Limited liability companies, limited partnerships, and corporations protect company assets from personal claims against the company’s owners. The protection of the corporate veil depends largely on the jurisdiction in which the company is formed, and entirely on whether the company is structured, documented, and managed properly and consistently.

U.S. domestic irrevocable trusts–As addressed briefly above, roughly one-third of states in the U.S. allow an individual to establish various types of irrevocable trusts that shield personal assets from creditor claims. Levels of protection vary from state to state, and residents of some states may not be permitted under local law to benefit from the asset protections of a state in which they do not reside.

Non-U.S. entities and trusts–Some trust jurisdictions outside the United States provide heightened protection from potential creditors. In a few cases, even claims brought by a government agency may be barred from properly-established irrevocable trusts or corporate entities governed by the laws of a foreign jurisdiction.

To the extent assets are properly titled to an effective strategy, assets can often be shielded from the claims of many potential creditors. But in all cases:

The strategy must be legally recognized,

The strategy exploits the most private, protective jurisdictions,

The asset owner must release significant control over the assets committed to the strategy,

Fiduciary title ownership must be effectively documented within the strategy, and

The fiduciary must rigorously maintain operational compliance of the strategy to preserve its protective veil.

It’s not about the Method; It’s about Intent

Regardless of the method used–technology-based solutions or sophisticated legally-recognized solutions–the circumstances matter and often, timing is everything. In the event a creditor (or the government) raises a claim against someone’s assets, the law will consider several factors:

Did the debtor (the owner trying to protect property) move so much of their wealth beyond their own reach that they’re effectively insolvent?

Did the debtor transfer in form, but not in substance (i.e., the debtor secretly retained control of the asset)?

When did the debtor employ the strategy? If the creditor’s claim had already arisen, it will likely be clawed back. If the debtor knew, or should have known that a claim existed… same result.

Did the debtor engage in a series of transactions that appear to be related and/or transactions that otherwise wouldn’t stand on their own?

Are the wealth-protecting tactics recognized by law?

These and a host of other considerations constitute “badges of fraud” that a court would consider in legally setting aside actions to hide or protect assets. None of them on their own is inherently problematic, but as more factors pile up, scrutiny increases.

The consequences of getting caught defrauding creditors with methods like these can be severe. Individuals convicted of violating federal money laundering laws face significant penalties. These include asset forfeiture, additional fines (often a multiple of the value of the property involved), and lengthy prison terms.

The government can seize not only the proceeds from illegal activities but any property used to facilitate the offense, including the real estate from which the activity took place. Further potential fallout includes reputational damage, penalties and interest on unpaid taxes, criminal liability for tax fraud, and for non-citizens, deportation.

Professionals in regulated fields (attorneys, accountants, asset managers) additionally risk disciplinary action including loss of their licenses and potential criminal liability for advising or assisting individuals with illicit actions to hide bitcoin or other assets.

Finally–and at the risk of being pedantic–those who engage in such behaviors for the purpose of hindering, delaying, or defrauding creditors might also consider what they signal to their children and others about the nature of their integrity.

A final word on Where to Protect

U.S.-based planning strategies will never protect you from the U.S. The federal government and its agencies are referred to as “super creditors”. They have extraordinary collection powers that far exceed those available to private parties or even most other institutional creditors. The government can bypass many of the procedural and substantive protections that otherwise apply in creditor–debtor relationships. In the case of U.S.-based strategies, the government can often directly seize assets held by U.S.-connected custodians.

To have any hope of sheltering assets from the reach of Uncle Sam, only proper strategies deployed outside the U.S. will provide any possibility of reliably (and legally) sheltering bitcoin or other assets from the reach of the government.

Bitcoin has won. But we’re still in Normieland

In a recent conversation with friend, colleague, and fellow Substacker Jacob Shapiro, I offered the idea of two seemingly-opposed ideas that must be held in our minds at the same time:

One: Barring an existential failure of bitcoin, it cannot help but go up forever in fiat terms.

AND

Two: Normieland will endure.

People with significant wealth in bitcoin will someday want to extract fiat value from their bitcoin. This necessarily means that bitcoiners must use the reliable strategies of Normieland to legally and effectively protect their bitcoin from the government and from anyone else who would seek to separate them from their bitcoin. There are ways that Normieland doesn’t recognize or respect, and ways that have long track records of success.

Choose accordingly (and please choose carefully).

Supplement – A quick recap of folks who didn’t successfully protect bitcoin in their possession from the government:

Attorney Steve Oshins in Nevada provides excellent resources tracking the state of U.S. domestic asset protection laws. See https://www.oshins.com/_files/ugd/b211fb_e159190aa9c04112af068c994dc2c144.pdf

For a vivid, if deeply cringy example, consider the case of Heather Morgan, aka “Razzlekahn“ and Ilya Liechtenstein. https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/pr/bitfinex-hacker-and-wife-plead-guilty-money-laundering-conspiracy-involving-billions, and https://www.justice.gov/usao-dc/pr/website-related-multi-billion-dollar-bitfinex-hack-established